Exhausted From a Long Day Hunting for the Newest Fashions to Bring Back.

Manner in the menses 1600–1650 in Western European clothing is characterized by the disappearance of the ruff in favour of broad lace or linen collars. Waistlines rose through the catamenia for both men and women. Other notable fashions included total, slashed sleeves and tall or broad hats with brims. For men, hose disappeared in favour of breeches.

The artist Rubens with his starting time wife c. 1610. Her long, rounded stomacher and jacket-like bodice are characteristic Dutch fashions

The silhouette, which was essentially close to the body with tight sleeves and a low, pointed waist to around 1615, gradually softened and broadened. Sleeves became very full, and in the 1620s and 1630s were often paned or slashed to show the voluminous sleeves of the shirt or chemise below.

Spanish fashions remained very conservative. The ruff lingered longest in Espana and the netherlands, merely disappeared beginning for men and later for women in France and England.

The social tensions leading to the English Ceremonious War were reflected in English fashion, with the elaborate French styles popular at the courts of James I and his son Charles I contrasting with the sober styles in sadd colours favoured past Puritans and exported to the early settlements of New England (encounter below).

In the early on decades of the century, a trend among poets and artists to prefer a fashionable pose of affective is reflected in mode, where the characteristic touches are dark colours, open collars, unbuttoned robes or doublets, and a generally disheveled appearance, accompanied in portraits by world-weary poses and sad expressions.

Fashions influenced by royal courts [edit]

Fabric and patterns [edit]

Scrolling floral embroidery decorates this Englishwoman's wearing apparel, petticoat, and linen jacket, accented with blue-tinted reticella neckband, cuffs, and headdress, c. 1614–xviii.

Figured silks with elaborate pomegranate or artichoke patterns are however seen in this period, especially in Spain, simply a lighter mode of scrolling floral motifs, woven or embroidered, was popular, especially in England.

The great flowering of needlelace occurred in this period. Geometric reticella deriving from cutwork was elaborated into truthful needlelace or punto in aria (called in England "signal lace"), which likewise reflected the popular scrolling floral designs.[1] [2] [3]

In England, embroidered linen silk jackets fastened with ribbon ties were fashionable for both men and women from c. 1600–1620, as was reticella tinted with yellow starch. Overgowns with split sleeves (often trimmed with horizontal rows of braid) were worn by both men and women.

From the 1620s, surface ornament savage out of fashion in favour of solid-colour satins, and functional ribbon bows or points became elaborate masses of rosettes and looped trim.

Portraiture and fantasy [edit]

In England from the 1630s, under the influence of literature and especially court masques, Anthony van Dyck and his followers created a fashion for having one'due south portrait painted in exotic, historical or pastoral dress, or in simplified gimmicky fashion with various scarves, cloaks, mantles, and jewels added to evoke a classic or romantic mood, and also to forestall the portrait actualization dated within a few years. These paintings are the progenitors of the fashion of the later 17th century for having ane's portrait painted in undress, and do not necessarily reflect article of clothing equally it was actually worn.[four]

Women'due south fashions [edit]

Elizabeth Poulett wears a low rounded neckline and a small ruff paired with a winged collar. Her tight sleeves have pronounced shoulder wings and deep lace cuffs. English court costume, 1616

Henrietta Maria, wife of Charles I of England, wears a airtight satin high-waisted bodice with tabbed skirts and open three-quarter sleeves over full chemise sleeves. She wears a ribbon sash. C. 1632–1635.

Gowns, bodices, and petticoats [edit]

In the early years of the new century, stylish bodices had high necklines or extremely low, rounded necklines, and short wings at the shoulders. Separate airtight cartwheel ruffs were sometimes worn, with the continuing collar, supported by a modest wire frame or supportasse used for more casual wear and condign more mutual subsequently. Long sleeves were worn with deep cuffs to match the ruff. The cartwheel ruff disappeared in fashionable England by 1613.[5]

By the mid-1620s, styles were relaxing. Ruffs were discarded in favor of wired collars which were called rebatos in continental Europe and, later, wide, flat collars. Past the 1630s and 1640s, collars were accompanied past kerchiefs similar to the linen kerchiefs worn past centre-class women in the previous century; oft the neckband and kerchief were trimmed with matching lace.

Bodices were long-waisted at the beginning of the century, only waistlines rose steadily to the mid-1630s before beginning to drop once again. In the second decade of the 17th century, short tabs developed attached to the lesser of the bodice covering the bum-roll which supported the skirts. These tabs grew longer during the 1620s and were worn with a stomacher which filled the gap between the two front end edges of the bodice. By 1640, the long tabs had virtually disappeared and a longer, smoother figure became stylish: The waist returned to normal height at the back and sides with a low betoken at the front end.

The long, tight sleeves of the early 17th century grew shorter, fuller, and looser. A mutual manner of the 1620s and 1630s was the virago sleeve, a full, slashed sleeve gathered into two puffs by a ribbon or other trim above the elbow.

In France and England, lightweight brilliant or pastel-coloured satins replaced nighttime, heavy fabrics. Equally in other periods, painters tended to avoid the difficulty of painting striped fabrics; information technology is clear from inventories that these were mutual.[6] Short strings of pearls were fashionable.

Unfitted gowns (called nightgowns in England) with long hanging sleeves, short open sleeves, or no sleeves at all were worn over the bodice and skirt and tied with a ribbon sash at the waist. In England of the 1610s and 1620s, a loose nightgown was ofttimes worn over an embroidered jacket called a waistcoat and a contrasting embroidered petticoat, without a farthingale.[seven] Black gowns were worn for the well-nigh formal occasions; they fell out of mode in England in the 1630s in favour of gowns to match the bodice and petticoat, but remained an important item of clothing on the Continent.

At to the lowest degree in the netherlands the open-fronted overgown or vlieger was strictly reserved for married women. Earlier marriage the bouwen, "a dress with a fitted bodice and a skirt that was closed all circular" was worn instead; information technology was known in England as a "Dutch" or "round gown".[8]

Skirts might be open in front to reveal an underskirt or petticoat until about 1630, or closed all around; airtight skirts were sometimes carried or worn looped up to reveal a petticoat.

Corsets were shorter to suit the new bodices, and might accept a very potent busk in the eye front extending to the depth of the stomacher. Skirts were held in the proper shape by a padded roll or French farthingale property the skirts out in a rounded shape at the waist, falling in soft folds to the flooring. The drum or bicycle farthingale was worn at the English courtroom until the death of Anne of Denmark in 1619.

Hairstyles and headdresses [edit]

To nigh 1613, pilus was worn feathered high over the forehead. Married women wore their hair in a linen coif or cap, often with lace trim. Tall hats like those worn by men were adopted for outdoor wear.

In a feature fashion of 1625–1650, hair was worn in loose waves to the shoulders on the sides, with the rest of the pilus gathered or braided into a high bun at the back of the caput. A curt fringe or bangs might exist worn with this style. Very stylish married women abandoned the linen cap and wore their hair uncovered or with a hat.

Style gallery 1600–1620 [edit]

-

one – 1602

-

ii – 1605

-

iii – 1609

-

iv – 1610s

-

5 – 1612

-

6 – 1614–18

-

7 – 1618–20

-

viii c. 1620

- Hilliard's Unknown Woman of 1602 wears typical Puritan fashion of the early years of the century. Her tall black felt hat with a rounded crown is called a capotain and is worn over a linen cap. She wears a black clothes and a white stomacher over a chemise with blackwork embroidery trim; her neckline is filled in with a linen partlet.

- Anne of Denmark wears a bodice with a depression, round neckline and tight sleeve, with a matching petticoat pinned into flounces on a drum or cartwheel farthingale, 1605. The loftier-fronted hairstyle was briefly fashionable. The jewels of Anne of Denmark are well-documented and depicted in her portraits.

- Isabella Clara Eugenia of Spain, Regent of the netherlands, wears a cartwheel ruff and wide, flat ruffles at her wrists. Her carve up-sleeved dress in the Spanish fashion is trimmed with wide bands of complect or fabric, 1609.

- Mary Radclyffe in the very depression rounded neckline and airtight cartwheel ruff of c.1610. The black silk strings on her jewelry were a passing fashion.

- Anne of Denmark wears mourning for her son, Henry, Prince of Wales, 1612. She wears a black wired cap and black lace.

- An Englishwoman (traditionally called Dorothy Cary, After Viscountess Rochford) wears an embroidered linen jacket with ribbon ties and embroidered petticoat under a black dress with hanging sleeves lined in gray. Her reticella lace collar, cuffs, and hood are tinted with yellow starch.

- Frans Hals' young woman wears a chain girdle over her blackness vlieger open-fronted gown, reserved for married women, and an elongated bodice with matching tight sleeves and petticoat. She is wearing a padded whorl to hold her brim in the fashionable shape. Dutch, 1618–xx.

- Elizabeth, Lady Mode of Wateringbury wears an embroidered jacket-bodice and petticoat under a red velvet dress. She wears a sheer partlet over an embroidered high-necked chemise, c. 1620.

Style gallery 1620s [edit]

-

ane – c. 1620

-

2 – 1620–21

-

iii – 1620s

-

four – 1625

-

5 – 1623–26

-

six – 1623–26

-

7 – c. 1626

-

8 – c. 1629–30

- Margaret Laton wears a blackness gown over an embroidered linen jacket tucked into the newly fashionable high-waisted petticoat of c. 1620. She wears a sheer apron or overskirt, a falling ruff, and an embroidered cap with lace trim. The jacket itself is in the longer manner of the previous decade.[9]

- Marie de' Medici in widowhood wears black with a black wired cap and veil, c. 1620–21.

- Anne of Austria, Queen of French republic, wears an open up bodice over a stomacher and virago sleeves, with a closed ruff. Note looser cuffs. C. 1621–25.

- Susanna Fourment wears an open high-necked chemise, crimson sleeves tied on with ribbon points, and a broad-brimmed lid with plumes, 1625.

- Élisabeth de French republic, Queen of Kingdom of spain, wears her pilus in a popular mode at the Spanish court, c. 1625.

- Isabella Brandt wears a black gown over a gold bodice and sleeves and a striped petticoat, 1623–26.

- Paola Adorno, Marchesa Brinole-Sale wears a black gown and a sheer ruff with large, soft figure-of-eight pleats seen in Italian portraits of this period. Her hair is caught in a cylindrical cap or caul of pearls. Genoa, c. 1626.

- Marie-Louise de Tassis wears a short-waisted gown with a sash over a tabbed bodice with a long stomacher and matching petticoat and virago sleeves, c. 1629–thirty.

Mode gallery 1630s [edit]

-

1 – 1630

-

two – 1630

-

3 – c. 1632

-

iv – 1632

-

five – 1632

-

6 – 1633

-

7 – 1635

-

8 – 1635

-

9 – 1638

- Large ruffs remained part of Dutch fashion long after they had disappeared in France and England. The dark gown has short puffed sleeves and is worn over tight undersleeves and a pink petticoat trimmed with rows of braid at the hem. The lace-edged frock shows creases from starching and ironing, 1630.

- Portrait of an unknown woman wearing the informal English fashion of a brightly coloured bodice and petticoat without an overgown. Her bodice has deep tabs at the waist and virago sleeves, 1630.

- Henrietta Maria as Divine Beauty in the masque Tempe Restored wears a high-necked chemise, a lace collar, and a jeweled cap with a feather, 1632. Masquing costumes such as this ane, designed by Inigo Jones, are often seen in portraits of this period.[vii]

- Henrietta Maria wears the formal English court costume of a gown with brusk open sleeves over a matching bodice with virago sleeves and a uncomplicated petticoat, 1632.

- Henrietta Maria wears a white satin tabbed bodice with total sleeves trimmed with silver braid or lace and a matching petticoat. Her bodice is laced up with a coral ribbon over a stomacher. A matching ribbon is fix in a V-shape at her front waist and tied in a bow to 1 side. She wears a lace-trimmed smock or partlet with a broad, square collar. A ribbon and a cord of pearls decorate her pilus, 1632.

- Henrietta Maria's riding costume consists of a jacket-bodice of blueish satin with long tabbed skirts and a matching long petticoat. She wears a broad-brimmed hat with ostrich plumes, 1633.

- A Lady from Spanish court wears an elegant, black apparel. Its simplicity is a testament to the austerity of the Spanish court; however, her high hair is quite fashionable, as well as the mass of curls on both sides of her face up c. 1635.

- Sara Wolphaerts van Diemen wears a double cartwheel ruff that remained pop in the netherlands through the period. She wears a black gown with a brocaded stomacher and virago sleeves, and a white linen cap, 1635.

- Helena Fourment wears a black robe, bodice, and petticoat worn with an open-necked chemise with a wide, starched lace collar, grey satin sleeves tied with rose-coloured ribbons, and a wide-brimmed black chapeau cocked upwardly on ane side and decorated with a hatband and plumes, 1638.

Style gallery 1640s [edit]

-

1 – 1640

-

2 – c. 1640

-

iii – 1641

-

4 – 1640s

-

five – 1643

-

six - 1645

-

7 - c. 1648

-

eight - c. 1648

- Elizabeth, Lady Capel wears a bright blue bodice and petticoat with yellowish ribbons and a lace-trimmed kerchief pinned at her cervix. Her daughters Mary and Elizabeth vesture gold-coloured bodices and petticoats, 1640.

- Portrait of Henrietta Maria in the style of Van Dyck shows her in a flame-colored satin dress without a collar or kerchief. She wears a fur piece draped over her shoulder, 1640.

- Agatha Bas wears a pointed stomacher nether a front end-lacing, high-waisted black dress. Her matching linen kerchief, neckband and cuffs are trimmed with lace, and she wears a high-necked chemise or partlet, the netherlands, 1641.

- Hester Tradescant'south costume is trimmed in lace in keeping with her station, but she wears the closed linen cap or coif, alpine hat, unrevealing neckline, and sober colours favoured by Puritans, c. 1645. Her long-fronted bodice and open skirt are conservative fashions at this date.

- Dutch fashions of the 1640s feature pocket-size, high-necked chemises, wide linen collars with matching kerchiefs and deep cuffs, and lavish employ of bobbin lace.

- Engraving of Cecylia Renata, Queen of Poland in riding dress (doublet, skirt, and hat), 1645.

- Claudia de' Medici equally a widow, in mourning wearing apparel (black cap, veil, and cloak) c. 1648.

- Archduchess Isabella Klara wears her lace neckband or tucker off-the-shoulder.

Men'south fashions [edit]

Shirts, doublets, and jerkins [edit]

Charles I wears a slashed doublet with paned sleeves, breeches, and tall narrow boots with turned-over tops, 1631.

Doublet of embroidered glazed linen, 1635–40, Five&A Museum no. 177–1900.

The result of the Edict of 1633: the French courtier abandons his paned sleeves and ribbons for plainer styles. He has a lovelock, in his pilus which tin can be seen hanging in front of his left sholder.

The Knuckles of Buckingham wears a wired collar with lace trim and a slashed doublet and sleeves. His hair falls in loose curls to his collar. C. 1625

Linen shirts had deep cuffs. Shirt sleeves became fuller throughout the period. To the 1620s, a collar wired to stick out horizontally, called a whisk, was popular. Other styles included an unstarched ruff-like collar and, later, a rectangular falling band lying on the shoulders. Pointed Van Dyke beards, named after the painter Anthony van Dyck, were fashionable, and men often grew a large, wide moustache, as well. Doublets were pointed and fitted close to the trunk, with tight sleeves, to well-nigh 1615. Gradually waistlines rose and sleeves became fuller, and both torso and upper sleeves might exist slashed to show the shirt beneath. By 1640, doublets were full and unfitted, and might be open at the front below the high waist to show the shirt.

Sleeveless leather jerkins were worn past soldiers and are seen in portraits, only otherwise the jerkin speedily fell out of fashion for indoor wear.

Hose and breeches [edit]

M Paned or pansied trunk hose or round hose, padded hose with strips of fabric (panes) over a full inner layer or lining, were worn early on in the period, over cannions, fitted hose that ended above the knee. Trunk hose were longer than in the previous menstruation, and were pear-shaped, with less fullness at the waist and more at mid-thigh.

Slops or galligaskins, loose hose reaching merely below the knee, replaced all other styles of hose by the 1620s, and were now generally called breeches. Breeches might be fastened upward the outer leg with buttons or buckles over a full lining.

From 1600 to c. 1630, hose or breeches were fastened to doublets by means of ties or points, short laces or ribbons pulled through matching sets of worked eyelets. Points were tied in bows at the waist and became more than elaborate until they disappeared with the very short waisted doublets of the late 1630s. Busy metal tips on points were called aiguillettes or aiglets, and those of the wealthy were fabricated of precious metals set with pearls and other gemstones.[10]

Spanish breeches, rather stiff ungathered breeches, were also pop throughout the era.

Outerwear [edit]

Gowns were worn early in the period, simply fell out of fashion in the 1620s.

Short cloaks or capes, usually hip-length, often with sleeves, were worn by fashionable men, commonly slung artistically over the left shoulder, even indoors; a style of the 1630s matched the cape fabric to the breeches and its lining to the doublet. Long cloaks were worn for inclement weather.

Hairstyles and Headgear [edit]

Early in the period, hair was worn collar-length and brushed dorsum from the brow; very fashionable men wore a unmarried long strand of hair called a lovelock over one shoulder. Hairstyles grew longer through the menstruation, and long curls were fashionable by the late 1630s and 1640s, pointing toward the ascendance of the wig in the 1660s, with king Louis XIII of France (1601–1643) starting to pioneer wig-wearing in 1624 when he had prematurely begun to baldheaded.[xi]

Pointed beards and broad mustaches were stylish.

To about 1620, the stylish hat was the capotain, with a tall conical crown rounded at the top and a narrow brim. By the 1630s, the crown was shorter and the skirt was wider, ofttimes worn cocked or pinned up on one side and busy with a mass of ostrich plumes.

Close-plumbing fixtures caps chosen coifs or biggins were worn just by immature children and old men nether their hats or alone indoors.

Manner gallery 1600s–1620s [edit]

-

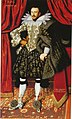

1 – 1603-10

-

ii – 1606–09

-

3 – c. 1610

-

4 – 1613

-

5 - 1615

-

6 - 1620

-

7 – 1623

-

eight – 1628

-

9 – 1629

-

10 - 1630

- James Half-dozen and I, 1603–1610, wears a satin doublet, wired whisk, brusque greatcoat, and hose over cannions. Narrow points are tied in bows at his waist. He wears the garter and collar of the Order of the Garter.

- The immature Henry, Prince of Wales and his companion clothing doublets with broad wings and tight sleeves, and matching full breeches with soft pleats at the waist. For hunting, they wear plainly linen shirts with flat collars and short cuffs at the wrist. Their soft boots plow downwards into cuffs below the knee, and are worn with linen kick hose. The prince wears a felt hat with a feather, 1606–09.

- Peter Saltonstall, in a fashionably melancholic pose c. 1610, wears an embroidered linen jacket nether a brown robe with split sleeves. The robe sleeves have buttons and parallel rows of fringed braid that make button loops. The apartment pleats or darts that shape his sheer collar and cuffs are visible. He wears an earring hung by a blackness cord.

- Richard Sackville, tertiary Earl of Dorset wears elaborate clothing, probably for the wedding of the Male monarch's daughter Elizabeth in 1613 (see notes on image page). His doublet, shoes, and the cuffs of his gloves are embroidered to match, and he wears a sleeved cloak on 1 arm and very full hose.

- Actor Nathan Field in a shirt busy with blackwork embroidery, 1615.

- Gustav Ii Adolf, Wedding attire from the wedding of Gustav II Adolf and Maria Eleonora 1620.

- James Hamilton wears the unstarched ruff that became popular in England in the 1620s. His hose reach to the lower thigh and are worn with cherry stockings and heeled shoes, 1623.

- Don Carlos of Spain wears a black patterned doublet with total black breeches, black stockings, and flat blackness shoes with roses. He carried a broad-brimmed blackness hat, 1628.

- Charles I. By the 1620s, doublets were still pointed but the waistline was rise higher up long tabs or skirts. Sleeves are slashed to the elbow and tight below. Points are more elaborate bows, and hose accept completed the transition to breeches.

- Gustav II Adolf, King of Sweden (1611–1632) wears the Swedish Protestant fashions of the 17th century. Boots adorned with flowers, doublet, cuffs and sheer neckband.

Fashion gallery 1630s–1640s [edit]

-

one – 1630s

-

2 – 1631–32

-

3 – 1634

-

4 – 1635

-

5 – c. 1638

-

vi – 1639

-

7 – 1642

-

eight – 1644

- Dutch way. The short-waisted doublet is slashed across the back. Points have elaborate ribbon rosettes (note matching points at hem of breeches).

- Philip 4 of Spain wears breeches and doublet of brownish and silver and a dark cloak all trimmed with argent lace. His sleeves are white and he wears white stockings, plain black shoes, and brown leather gloves, 1631–32.

- Henri II of Lorraine, Duke de Guise, in the buff leather jerkin and gorget (neck armor) of a soldier. His jerkin is open from the mid-chest, and his breeches lucifer his cape, 1634.

- Charles I's doublet of 1635 is shorter waisted, and points accept disappeared. He wears a wide-brimmed hat and boots.

- Royalist style: Brothers Lord John Stuart and Lord Bernard Stuart wear contrasting satin doublets and breeches, satin-lined short cloaks, and high collars with lavish lace scallops. Their high-heeled boots have deep cuffs and are worn over kick hose with lace tops, c. 1638.

- A Dutch civic guardsman wears a short-waisted leather buff jerkin and a broad sash, both fashionable amongst soldiers. 1639.

- The young Charles, Prince of Wales, (later Charles II) wears a soldier'south buff jerkin, sash, and half armor over a fashionable doublet and breeches trimmed with ribbon bows.

- Philip IV of Spain in war machine dress, 1644, wears a broad linen neckband and matching cuffs. His sleeved curt gown or cassock of red with metallic embroidery is worn over a vitrify jerkin and silver-gray sleeves. He carries a broad-brimmed black lid cocked on one side.

Footwear [edit]

Heeled shoes with shoe roses

Boots with boothose, early (left) and late (right) 1630s

Bucket heeled boots with butterflies and spurs of King Ladislaus IV of Poland, c. 1640; butterflies were meant to reduce chafing from the spur straps

Flat shoes were worn to around 1610, when a low heel became popular. The ribbon tie over the instep that had appeared on late sixteenth century shoes grew into elaborate lace or ribbon rosettes called shoe roses that were worn by the most fashionable men and women.

Backless slippers called pantofles were worn indoors.

By the 1620s, heeled boots became popular for indoor equally well equally outdoor vesture. The boots themselves were usually turned down below the knee; kick tops became wider until the "bucket-elevation" boot associated with The Three Musketeers appeared in the 1630s. Spurs straps featured decorative butterfly-shaped spur leathers over the instep.

Wooden clogs or pattens were worn outdoors over shoes and boots to keep the high heels from sinking into soft dirt.

Stockings had elaborate clocks or embroidery at the ankles early in the period. Boothose of stout linen were worn under boots to protect fine knitted stockings; these could be trimmed with lace.

Children'due south fashion [edit]

Toddler boys wore gowns or skirts and doublets until they were breeched.

-

1 – English, 1606

-

ii – Dutch, 1st Qtr 17th century

-

4 – Dutch, 1st 3rd 17th century

-

5 – Spanish, 1630–33

-

6 – Dutch, 1634

-

7 – Dutch, 1634

-

10 – Dutch, 1641

-

11 – French, Male monarch Louis XIV and his brother, mid-1640s

Simplicity of apparel [edit]

In Protestant and Cosmic countries, attempts were made to simplify and reform the extravagances of dress. Louis XIII of France issued sumptuary laws in 1629 and 1633 that prohibited lace, gold trim and lavish embroidery for all but the highest nobility and restricting puffs, slashes and bunches of ribbon.[12] The effects of this reform effort are depicted in a series of popular engravings by Abraham Bosse.[13]

Puritan wearing apparel [edit]

Puritans advocated a conservative form of fashionable attire, characterized by sadd colors and pocket-size cuts. Gowns with low necklines were filled in with high-necked smocks and wide collars. Married women covered their hair with a linen cap, over which they might wear a tall black hat. Men and women avoided brilliant colours, shiny fabrics and over-ornamentation.

Reverse to pop conventionalities, well-nigh Puritans and Calvinists did not wear black for everyday, peculiarly in England, Scotland and colonial America. Black dye was expensive, faded quickly and black habiliment was reserved for the well-nigh formal occasions (including having i's portrait painted), for elders in a community and for those of higher rank. Richer puritans, like their Dutch Calvinist contemporaries, probably did article of clothing it ofttimes but in silk, often patterned. Typical colours for nearly were brown, murrey (mulberry, a brownish-maroon), boring greens and tawny colours. Wool and linen were preferred over silks and satins, though Puritan women of rank wore modest amounts of lace and embroidery as appropriate to their station, assertive that the various ranks of order were divinely ordained and should be reflected even in the well-nigh small dress. William Perkins wrote "...that apparel is necessary for Scholar, the Tradesman, the Countryman, the Admirer; which serveth not simply to defend their bodies from common cold, merely which belongs too to the identify, degree, calling, and condition of them all" (Cases of Conscience, 1616).[fourteen]

Some Puritans rejected the long, curled hair as effeminate and favoured a shorter manner which led to the nickname Roundheads for adherents of the English Parliamentary party but the taste for lavish or unproblematic dress cutting across both parties in the English Civil War.[15]

Working class article of clothing [edit]

-

1 – c.1608

-

2 – c.1620

-

3 – 1627

-

4 – c.1635

-

5 – 1636

-

6 – 1643

- Flemish country folk: Men wear tall capotain hats; women habiliment like hats or linen headdresses, 1608.

- English state folk watching Morris dancers and a hobby horse clothing broad-brimmed hats. The woman wears a jacket-bodice and contrasting petticoat. Men wear total breeches and doublets, c. 1620.

- Army Habiliment: Buff coat fabricated of moose hide, and breeches made of wadmal with linen linings, worn by Gustav 2 Adolf at the Battle of Dirschau in August 1627

- Musketeer and pikeman, c. 1635. The pikeman on the right wears a total-skirted vitrify coat. Spanish, earlier 1635.

- Men in a tavern wear floppy hats, wrinkled stockings and long, high-waisted jerkins, some with sleeves, and blunt-toed shoes.

- Man hunting small game wears a grayness buttoned jerkin with brusk sleeves and matching breeches over a red doublet. He wears a fur-lined hat and grey gloves, Germany, 1643.

Notes [edit]

- ^ Drupe 2004.

- ^ Kliot, Jules and Kaethe: The Needle-Made Lace of Reticella.

- ^ Montupet, Janine, and Ghislaine Schoeller: Lace: The Elegant Web

- ^ See Gordenker 2001, p.[ page needed ] and Winkel 2007, pp. lxx, 71

- ^ See Costume notes to portrait of Mary Radclyffe, Denver Museum of Art Archived 11 Feb 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Marieke de Winkel in:Rudi Ekkart and Quentin Buvelot (eds), Dutch Portraits, The Historic period of Rembrandt and Frans Hals, Mauritshuis/National Gallery/Waanders Publishers, Zwolle, p.73, 2007, ISBN 978-1-85709-362-ix

- ^ a b See Aileen Ribeiro, Fashion and Fiction: Dress in Fine art and Literature in Stuart England

- ^ Marieke de Winkel in:Rudi Ekkart and Quentin Buvelot (eds), Dutch Portraits, The Age of Rembrandt and Frans Hals, Mauritshuis/National Gallery/Waanders Publishers, Zwolle, p.67, 2007, ISBN 978-1-85709-362-nine

- ^ The jacket has been preserved and can exist seen at the in Victoria and Albert Museum web site.

- ^ Scarisbrick, Diana, Tudor and Jacobean Jewellery, pp. 99–100

- ^ marcelgomessweden. "Louis XIII « The Beautiful Times". Thebeautifultimes.wordpress.com. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ Kõhler, Carl: A History of Costume, p. 289

- ^ Lefébure, Ernest: Embroidery and Lace: Their Manufacture and History from the Remotest Artifact to the Present Day, p.230

- ^ See Cases of Conscience, 1616 Archived 16 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ribeiro, Aileen: Dress and Morality, Berg Publishers 2003, ISBN 1-85973-782-X, pp. 12–16

References [edit]

- Berry, Robin L. (2004). Reticella: a walk through the beginnings of Lace (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- Gordenker, Emilie E.S. (2001). Van Dyck and the Representation of Clothes in Seventeenth-Century Portraiture. Brepols. ISBN2-503-50880-4.

- Kliot, Jules and; Kliot, Kaethe (1994). The Needle-Made Lace of Reticella. Berkeley, CA: Lacis Publications. ISBN0-916896-57-9.

- Kõhler, Carl (1963) [1928]. A History of Costume (reprint from Harrap translation from the High german ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN0-486-21030-8.

- Lefébure, Ernest (1888). Cole, Alan Due south. (ed.). Embroidery and Lace: Their Manufacture and History from the Remotest Artifact to the Present Day. London: H. Grevel and Co. – via Online Books.

- Montupet, Janine; Schoeller, Ghislaine; Fouriscot, Mike (1990). Lace: The Elegant Web. New York: H.N. Abrams. ISBN0-8109-3553-viii.

- Ribeiro, Aileen (2005). Fashion and Fiction: Wearing apparel in Art and Literature in Stuart England. Yale. ISBN0-300-10999-7.

- Scarisbrick, Diana (1995). Tudor and Jacobean Jewellery. London: Tate Publishing. ISBN1-85437-158-iv.

- Winkel, Marieke de (2007). "The 'Portrayal' of Clothing in the Aureate Age". In Ekkart, Rudi; Buvelot, Quentin (eds.). Dutch Portraits, The Age of Rembrandt and Frans Hals, Mauritshuis/National Gallery/Waanders. Zwolle. pp. 64–73. ISBN978-1-85709-362-9.

Further reading [edit]

- Ashelford, Jane (1996). The Art of Clothes: Vesture and Club 1500–1914. Abrams. ISBN0-8109-6317-5.

- Arnold, Janet (1986) [1985]. Patterns of Style: the cut and construction of dress for men and women 1560–1620 (Revised ed.). Macmillan. ISBN0-89676-083-nine.

External links [edit]

- Baroque Fashion 1600s

- Costume History: Cavalier/Puritan

- Women'due south Fashions of the 17th Century (engravings by Wenceslaus Hollar)

- Etchings of French 1620s men'due south fashion (more often than not) past Abraham Bosse

- Surviving embroidered linen jacket c. 1620 at the Museum of Costume

- Surviving embroidered linen jacket c. 1610–1615 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

0 Response to "Exhausted From a Long Day Hunting for the Newest Fashions to Bring Back."

Post a Comment